JAMMU & KASHMIR

Jammu and Kashmir, union territory of India, located in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent in the vicinity of the Karakoram and western Himalayan mountain ranges. The administrative capitals are Srinagar in summer and Jammu in winter.

Land

The vast majority of the territory is mountainous, and the physiography is divided into seven zones that are closely associated with the structural components of the western Himalayas. From southwest to northeast these zones consist of the plains, the foothills, the Pir Panjal Range, the Vale of Kashmir, the Great Himalayas zone, the upper Indus River valley, and the Karakoram Range. The climate varies from alpine in the northeast to subtropical in the southwest; in the alpine area, average annual precipitation is about 3 inches (75 mm), but, in the subtropical zone (around Jammu), rainfall amounts to about 45 inches (1,150 mm) per year. The entire region is prone to violent seismic activity, and light to moderate tremors are common.

The plains

The narrow zone of plains country in the Jammu region is characterized by interlocking sandy alluvial fans that have been deposited by streams discharging from the foothills and by a much-dissected pediment (eroded bedrock surface) covered by loams and loess (wind-deposited silt) of Pleistocene age (about 11,700 to 2,600,000 years old). Precipitation is low, amounting to about 15 to 20 inches (380 to 500 mm) per year, and it occurs mainly in the form of heavy but infrequent rain showers during the summer monsoon (June to September). The countryside has been almost entirely denuded of trees, and thorn scrub and coarse grass are the dominant forms of vegetation.

The foothills

The foothills of the Himalayas, rising from about 2,000 to 7,000 feet (600 to 2,100 metres), form outer and inner zones. The outer zone consists of sandstones, clays, silts, and conglomerates, influenced by Himalayan folding movements and eroded to form long ridges and valleys called duns. The inner zone consists of more-massive sedimentary rock, including red sandstones of Miocene age (roughly 5.3 to 23 million years old), that has been folded, fractured, and eroded to form steep spurs and plateau remnants. River valleys are deeply incised and terraced, and faulting has produced a number of alluvium-filled basins, such as those surrounding Udhampur and Punch. As precipitation increases with elevation, the lower scrubland gives way to pine forests.

The Pir Panjal Range

The Pir Panjal Range constitutes the first (southernmost) mountain rampart associated with the Himalayas in the UT and is the westernmost of the Lesser Himalayas. It has an average crest line of 12,500 feet (3,800 metres), with individual peaks rising to some 15,000 feet (4,600 metres). Consisting of an ancient rock core of granites, gneisses, quartz rocks, and slates, it has been subject to considerable uplift and fracturing and was heavily glaciated during the Pleistocene Epoch. The range receives heavy precipitation in the forms of winter snowfall and summer rain and has extensive areas of pasture above the tree line.

The Vale of Kashmir

The Vale of Kashmir is a deep, asymmetrical basin lying between the Pir Panjal Range and the western end of the Great Himalayas at an average elevation of 5,300 feet (1,620 metres). During the Pleistocene Epoch it was occupied at times by a body of water known as Lake Karewa; it is now filled by lacustrine (still water) sediments as well as alluvium deposited by the upper Jhelum River. Soil and water conditions vary across the valley. The climate is characterized by annual precipitation of about 30 inches (750 mm), derived partially from the summer monsoon and partially from storms associated with winter low-pressure systems. Snowfall often is accompanied by rain and sleet. Temperatures vary considerably by elevation; at Srinagar the average minimum temperature is in the upper 20s F (about −2 °C) in January, and the average maximum is in the upper 80s F (about 31 °C) in July. Up to about 7,000 feet (2,100 metres), woodlands of deodar cedar, blue pine, walnut, willow, elm, and poplar occur; from 7,000 to 10,500 feet (3,200 metres), coniferous forests with fir, pine, and spruce are found; from 10,500 to 12,000 feet (3,700 metres), birch is dominant; and above 12,000 feet are meadows with rhododendrons and dwarf willows as well as honeysuckle.

The Great Himalayas zone

Geologically complex and topographically immense, the Great Himalayas contain ranges with numerous peaks reaching elevations of 20,000 feet (6,100 metres) or more, between which lie deeply entrenched, remote valleys. The region was heavily glaciated in Pleistocene times, and remnant glaciers and snowfields are still present. The zone receives some rain from the southwest monsoon in the summer months—and the lower slopes are forested—but the mountains constitute a climatic divide, representing a transition from the monsoon climate of the Indian subcontinent to the dry, continental climate of Central Asia.

The upper Indus River valley

The valley of the upper Indus River is a well-defined feature that follows the geologic strike (structural trend) westward from the Tibetan border to the point in the Pakistani sector of Kashmir where the river rounds the great mountainous mass of Nanga Parbat to run southward in deep gorges that cut across the strike. In its upper reaches the river is flanked by gravel terraces; each tributary builds an alluvial fan out into the main valley. The town of Leh stands on such a fan, 11,500 feet (3,500 metres) above sea level, with a climate characterized by an almost total lack of precipitation, by intense insolation (exposure to sunlight), and by great diurnal and annual ranges of temperature. Life depends on meltwater from the surrounding mountains, and vegetation is alpine (i.e., consists of species above the tree line), growing on thin soils.

The Karakoram Range

The great granite-gneiss massifs of the Karakoram Range—which straddles the Indian and Pakistani sectors of Kashmir—contain some of the world’s highest peaks. These include K2 (also called Mount Godwin Austen) on the border of the Pakistani sector and one of the Chinese-administered enclaves, with an elevation of 28,251 feet (8,611 metres); at least 30 other peaks exceed 24,000 feet (7,300 metres). The range, which is still heavily glaciated, rises starkly from dry, desolate plateaus that are characterized by extremes of temperature and shattered rock debris. The Karakoram, along with other areas in and around the Himalayan region, is often called the “roof of the world.”

Animal life

Among the wild mammals found in the UT are the Siberian ibex, the Ladakh urial (a species of wild sheep with a reddish coat), the rare hangul (or Kashmir stag) found in Dachigam National Park, the endangered markhor (a large goat) inhabiting mainly protected areas of the Pir Panjal Range, and black and brown bears. There are many species of game birds, including vast numbers of migratory ducks.

People

The cultural, ethnic, and linguistic composition of Jammu and Kashmir varies across the UT by region. About two-thirds of the population adheres to Islam, a greater proportion than in any other Indian UT; Hindus constitute most of the remaining third. There also are small minorities of Sikhs and Buddhists. Urdu is the UT’s official language.

The Jammu region

Jammu, winter capital of the maharajas (the former Hindu rulers of the region) and second largest city in the UT, was historically the seat of the Dogra dynasty. More than two-thirds of the region’s residents are classified as Hindu. Most of Jammu’s Hindus live in the southeastern portion of the region and are closely related to the Punjabi-speaking peoples in Punjab state; many speak the Dogri language. The majority of the UT’s Sikhs also live in the Jammu region. To the northwest, however, the proportion of Muslims increases, with Muslims making up a dominant majority in the area around the western town of Punch.

Kashmiris of the vale and highlands

The Vale of Kashmir, surrounded by the highlands of the broader Kashmir region, always has had something of a unique character. The vast majority of the people are Muslims who speak Kashmiri or Urdu. Culturally and ethnically, their closest links are with peoples in the northwestern highlands of the Gilgit district of the Pakistani-administered sector of Kashmir. The Kashmiri language is influenced by Sanskrit and belongs to the Dardic branch of Indo-Aryan languages, which also are spoken by the various hill peoples of Gilgit; Kashmiri has rich folklore and literary traditions. The great majority of the population resides in the lower reaches of the vale. Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir’s largest city, is located on the Jhelum River.

Settlement patterns

The UT’s physiographic diversity is matched by a considerable variety of human occupation. In the plains and foothills of the southwestern region, colonization movements from the Punjab areas over a long period of time have produced numerous agricultural settlements. In the dun regions and lower valleys of the foothills, where alluvial soils and the availability of water for irrigation make agriculture possible, the population is sustained by crops of wheat and barley, which are gathered in the spring (rabi) harvest, and of rice and corn (maize), gathered in the late summer (kharif) harvest; livestock also are raised. The upper sections of the valleys support a sparser population that depends on a mixed economy of corn, cattle, and forestry. Herders migrate to higher pastures each spring to give their flocks the necessary forage to produce milk and clarified butter, or ghee, for southern lowland markets. In winter the hill dwellers return to lower areas to work in government-owned forests and timber mills. Agricultural hamlets and nucleated villages predominate throughout the UT; cities and towns such as Jammu and Udhampur function essentially as market centres and administrative headquarters for the rural populations and estates in the vicinity.

Economy

Agriculture

The majority of the people of Jammu and Kashmir are engaged in subsistence agriculture of diverse kinds on terraced slopes, each crop adapted to local conditions. Rice, the staple crop, is planted in May and harvested in late September. Corn, millet, pulses (legumes such as peas, beans, and lentils), cotton, and tobacco are—with rice—the main summer crops, while wheat and barley are the chief spring crops. Many temperate fruits and vegetables are grown in areas adjacent to urban markets or in well-watered areas with rich organic soils. Sericulture (silk cultivation) is also widespread. Large orchards in the Vale of Kashmir produce apples, pears, peaches, walnuts, almonds, and cherries, which are among the UT’s major exports. In addition, the vale is the sole producer of saffron in the Indian subcontinent. Lake margins are particularly favourable for cultivation, and vegetables and flowers are grown intensively in reclaimed marshland or on artificial floating gardens. The lakes and rivers also provide fish and water chestnuts.

Resources and power

The UT’s limited mineral and fossil fuel resources are concentrated primarily in the Jammu region. Small reserves of natural gas are found near the city of Jammu, and bauxite and gypsum deposits occur in the vicinity of Udhampur. Other minerals include limestone, coal, zinc, and copper. The pressure of population on land is apparent everywhere, and all available resources are utilized.

All the principal cities and towns, and a majority of the villages are electrified, and hydroelectric and thermal generating plants have been constructed to provide power for industrial development based on local raw materials. Major power stations are located at Chineni and Salal and on the upper Sind and lower Jhelum rivers.

Manufacturing

Metalware, precision instruments, sporting goods, furniture, matches, and resin and turpentine are the major manufactures of Jammu and Kashmir, with the bulk of the UT’s manufacturing activity located in Srinagar. Many industries have developed from rural crafts, including handloom weaving of local silk, cotton, and wool, carpet weaving, wood carving, and leatherwork. Such industries, together with the making of silverwork, copperwork, and jewelry, were stimulated first by the presence of the royal court and later by the growth of tourism; however, they also owe something to the important position achieved by Srinagar in west Himalayan trade. In the past the city acted as an entrepôt for the products of the Punjab region on the one hand and of the high plateau region east of the Karakoram, Pamir ranges on the other hand. Routes still run northwestward into Gilgit via the Raj Diangan Pass .

Tourism

Although facilities for visitors to Jammu and Kashmir have improved considerably since the late 20th century, the UT’s potential in the tourist sector has remained generally untapped. In addition to historical and religious sites, visitor destinations include the snow-sports centre at Gulmarg in the northern Pir Panjal Range west of Srinagar and the UT’s many lakes and rivers. Mountain trekking is popular from July through September.

TransportationUT’s infrastructure. As a result of the India-Pakistan dispute over the Kashmir region, the route through the Jhelum valley from Srinagar to Rawalpindi, Pak., was closed in the late 1940s. This made it necessary to transform a longer and more difficult cart road through Banihal Pass into an all-weather highway in order to link Jammu with the Vale of Kashmir; included was the construction of the Jawahar Tunnel, which at the time of its completion in 1959 was one of the longest in Asia. This road, however, is often made impassable by severe weather, which causes shortages of essential commodities in the vale. A road also connects Srinagar with Kargil and Leh. In addition, a route through the Pir Panjal Range that followed the ancient Mughal Road opened in 2010, significantly reducing the travel distance between Punch and the vale.

Jammu is the terminus of the Northern Railway of India. In the 1990s construction got under way on a rail link between Jammu and Baramula (via Srinagar) near the northern end of the vale. Work proceeded slowly, but by the early 21st century the segments had been completed between Jammu and Udhampur and from Baramula to Anantnag southeast of Srinagar in the vale. Srinagar and Jammu are linked by air to Delhi and other Indian cities, and there is air service between Srinagar, Leh, and Delhi.

Government and society

Health and welfare

Medical service is provided by hospitals and dispensaries scattered throughout the UT. Influenza, respiratory ailments such as asthma, and dysentery remain common health problems. Cardiovascular disease, cancer, and tuberculosis have increased in the Vale of Kashmir since the late 20th century.

Education

Education is free at all levels. Literacy rates are comparable to the national average. The two major institutes of higher education are the University of Kashmir at Srinagar and the University of Jammu, both founded in 1969. In addition, agricultural schools have been established in Srinagar (1982) and Jammu (1999). A specialized institute of medical sciences was founded in Srinagar in 1982.

Information

-

FOLK ARTIST AND YOUNG ARTIST HONOUR AWARD 2024

FOLK ARTIST AND YOUNG ARTIST HONOUR AWARD 2024Oct 09, 2024 Comments Off on FOLK ARTIST AND YOUNG ARTIST HONOUR AWARD 2024

Events

-

Hindi play “Mujhe Amrita Chahiye” on the...

Hindi play “Mujhe Amrita Chahiye” on the...Mar 24, 2025 Comments Off on Hindi play “Mujhe Amrita Chahiye” on the occasion of World Theatre Day on 27 March 2025

-

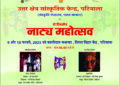

North Zone Cultural Centre, Patiala, Ministry of Culture,...

North Zone Cultural Centre, Patiala, Ministry of Culture,...Feb 04, 2025 Comments Off on North Zone Cultural Centre, Patiala, Ministry of Culture, Government of India is organizing a two-day Drama Festival on 09 and 10 February 2025 at Kalidas Auditorium, Virsa Vihar Centre, Patiala. You all are cordially invited.

Videos

Follow us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

Related Links

Archives

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- March 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- October 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- April 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- November 2014

- October 2014

- August 2014

- March 2014